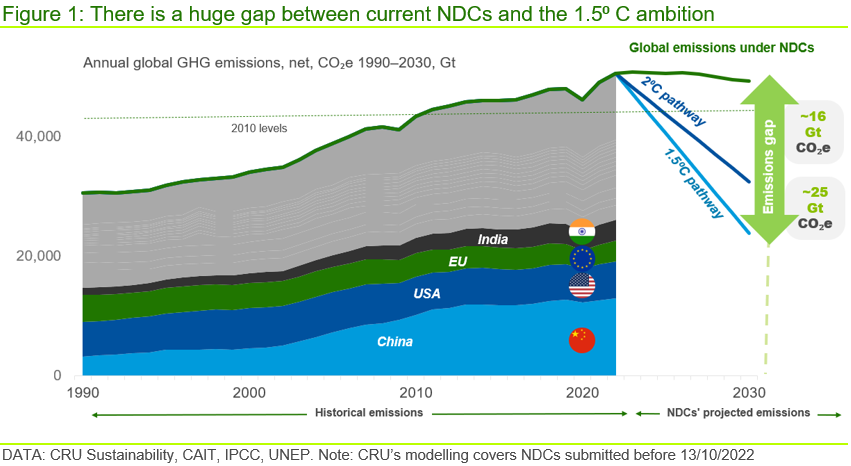

- Current Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) set emissions targets that are insufficient to limit global warming to +1.5°C or even +2°C above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century.

- The NDCs implementation framework is designed to ratchet-up and we expect further commitments and actions across all sectors. However, given current geopolitical events, the timing of this acceleration is increasingly uncertain.

- The longer the world community delays more concrete action, the more of the remaining carbon budget will be used by easier-to-abate sectors. Hard-to-abate sectors will have less time to adapt and put in place the needed infrastructure and investments. This will make it more difficult and costly to decarbonise economies later and raises the risks of future transition or climate shocks.

NDCs set commitments to decarbonise and adapt to climate change

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are a much discussed but often misunderstood part of climate policy. Simply, NDCs are overarching country-specific pledges to reduce national emissions and adapt to climate change. They provide broad targets towards decarbonisation. However, on their own they will not deliver the actions needed.

NDCs and the framework they operate in have taken considerable time and effort to get approved. Under the current framework, governments agreed to ratchet up their NDCs but new geopolitical challenges might weaken their political resolve to do so.

The window for successfully decarbonising economies is limited and this is why an acceleration in climate ambition is needed to avoid disastrous consequences from climate change. Delays in decarbonising economies risk a more disorderly and costly transition down the road, or a failed transition, where physical climate change risks pose existential risks to civilisation. This provides the background and need for greater progress at COP27.

Current NDCs will not limit global temperature increases to 2°C, let alone 1.5°C

The principal aim of the Paris Agreement was to limit the global average temperature increase to +2°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100 at a minimum, and preferably to +1.5°C. This aim was reaffirmed in the Glasgow Climate Pact signed at COP26 in November 2021 which “recognizes that limiting global warming to 1.5 °C requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, including reducing global carbon dioxide emissions by 45 per cent per cent by 2030 relative to the 2010 level and to net zero around mid-century as well as deep reductions in other greenhouse gases”.

NDCs embody efforts by each country to reduce national GHG emissions and adapt to impacts from climate change. NDCs are designed to promote wide participation and help for credible decarbonisation plans. The UN states “the best NDCs aim high and reach far. Grounded in sound analysis and data”.

The transition to a low carbon and regenerative economy is a vast undertaking, hence the need to revisit and enhance them on a regular basis. However, NDCs are often complex, difficult to understand, and each is bespoke, reflecting a country’s particular circumstances. Implementing, financing and monitoring them is extremely challenging.

The process that leads to NDCs is a carefully crafted compromise to encourage engagement and participation. Crucially, NDCs set the aims and roadmap that actions can be framed by, but NDCs need to be complemented by policies, subsidies, taxes, support, behavioural change and technological developments to curb global emissions. Progress on NDCs at COP27 is needed to ensure the world does not fall further behind on its climate aims.

The 1.5°C carbon budget could be exhausted within the decade

The carbon budget is the cumulative net global quantity of future carbon emissions that would limit the rise in the average global temperature with a given probability.

Climate modelling is probabilistic. In early-2020, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated in its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) that: “the current central estimate of the remaining carbon budget from 2020 onwards for limiting warming to 1.5°C with a probability of 50% has been assessed as 500 GtCO2 and as 1150 GtCO2 for a probability of 67% for limiting warming to 2° C...”.

This is only about a fifth of cumulative carbon emissions during the period of 1850 to 2019. The IPCC reports state “historical cumulative net CO2 emissions from 1850 to 2019 were 2,400 ± 240 GtCO2”. Moreover, carbon emissions are still rising. In the absence of any reductions in annual carbon emissions, the world community will have used up its entire remaining carbon budget consistent with limiting global temperature increases to an average 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by the early-2030s at the latest.

Together, the current trajectory of NDCs leads the world to a ~14% rise in global emissions compared to 2010 levels, rather than a fall. Moreover, most NDCs remain vague on how governments intend to achieve their climate goals. A +1.5°C future requires an annual global ~9% fall in emissions from now to 2030; while a +2°C future requires falls of around 5% per annum. There would need to be a huge increase in spending, vastly more policy support, further technological developments and considerably more progress in hard-to-abate sectors to get us close to either target.

How the remaining carbon budget will be allocated will have substantial implications for hard-to-abate sectors

We expect that governments will ratchet up their NDCs and that climate action will increase across all sectors. Increasing pressures to decarbonise, and the policies as well as technologies that will drive it will shape the supply, demand and costs of many commodities as well as their value chains over the coming decades.

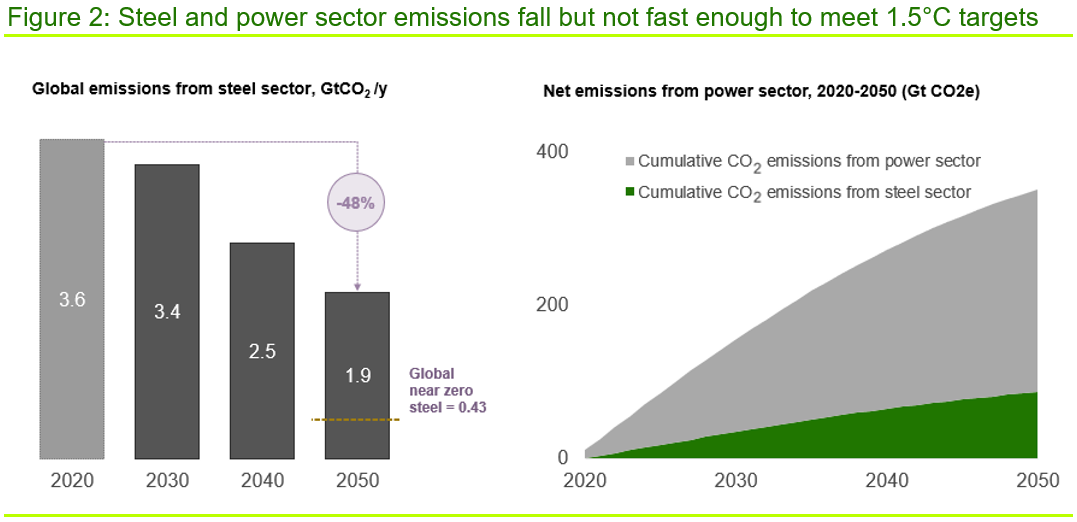

Requirements at the sector levels will likely become more detailed and onerous over time. How the remaining carbon budget will be used will have substantial implications for hard-to-abate sectors such as steel or fertilisers.

For hard-to-abate sectors, the longer it takes to decarbonise the rest of the economy, the more challenging decarbonisation is likely to become, as more of the global carbon budget will be consumed than is technically necessary. The reduced carbon budget available for hard-to-abate sectors, leaves less time and scope to innovate and develop the necessary infrastructure to enable the required pace of decarbonisation to deliver on the aims of the Paris Agreement.

Hard-to-abate sectors will be more exposed in a disorderly transition due to the relatively high capital intensity of abatement technologies and long lead times to deploy them.

Delaying the transition will mean that more is needed to be done in a shorter period, resulting in more draconian and costly measures. Furthermore, if key infrastructure is not in place and nascent technologies are not commercialised there will be fewer and more costly decarbonisation options.

Climate goals will require huge changes to energy markets

Data: CRU Long Term Steel Outlook, CRU Long Term Thermal Coal Outlook

Notes: (1) Near-zero steel is defined by Responsible Steel GHG Requirement ‘near zero’ Performance Level 4 threshold, which has been developed in consultation with the steel industry, utilising emissions data from CRU’s Steel Cost Service.

Energy markets will be a big determining factor in how quickly the world decarbonises and if we are able to get close to the Paris Agreement aims. The speed of transition to low carbon energy and electrification of infrastructure are essential determinants in meeting these aims. However, this will require a huge quantity of decarbonisation within existing energy grids, at a time when electricity as a proportion of our primary energy demand will grow. Moreover, to decarbonise hard-to-abate sectors, large amounts of additional electricity will be needed for applications, such as green hydrogen production. This is detailed in CRU’s Long Term Steel Market Outlook and CRU’s Low Emissions Ammonia Service. Please contact us to learn more.

Changes in the steel and power sectors will be crucial if the world is to decarbonise but this will be costly. CRU’s Steel Long Term Market Outlook calculates that the steel sector will cost the global economy over $0.6 trillion more annually by 2050 in real terms due to decarbonisation. The steel sectors transition will be demanding on energy systems and supporting infrastructure, using vastly more natural gas and ten times the electricity; but even with this, net zero targets in 2050 are expected to be missed.

Energy markets face a trilemma of competing issues – ensuring energy security, providing access to affordable, clean energy and ensuring sustainability of supply. The war in Ukraine has added to this pressure. Energy security has risen up the policy agenda globally and this may spur increased long-term investment in low carbon energy.

Governments likely to resist pressure for big new commitments at COP27

At last year’s COP26, it was agreed that ratcheting up climate change ambitions on a more frequent basis is needed. Governments agreed to submit more ambitious NDCs before COP27, hosted by the Egyptian government between 6–18 November 2022. Despite this, submissions have been limited, with fewer than 25 updated submissions since the end of COP26. It is now less than one month until COP27. We expect more, but not all remaining parties, to submit updated proposals in the coming weeks.

Governments will be under pressure to make even more ambitious commitments at COP27. However, faced with record-high inflation rates, the uneven and fragile post Covid-19 economic recovery, major fiscal pressures, global conflict and the energy crisis, significant breakthroughs will be hard to achieve, especially in terms of binding – and potentially costly – emission reduction goals.

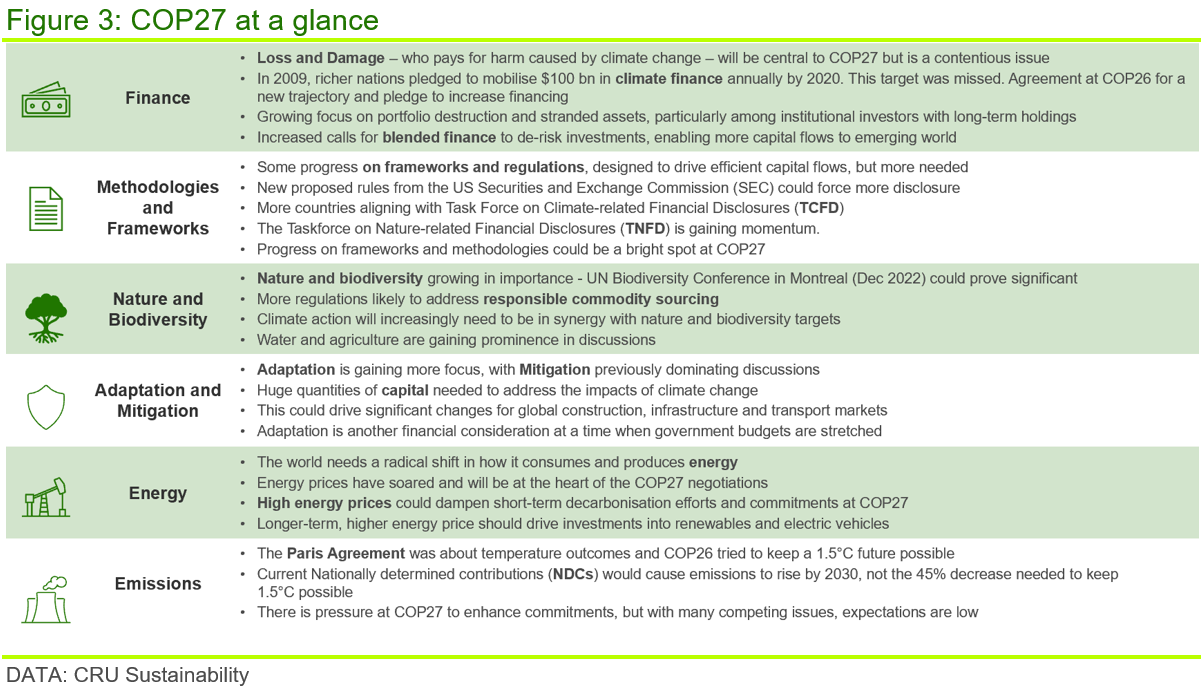

Governments may temper their policies due to these short-term issues, but they may agree to do more later. The risks of such backloading of action mean that the longer that action is delayed the costlier it could be, and more problems will be created for a later date. Having said this, there has also been an increased focus on implementation within long-term EU energy policies and the US Inflation Reduction Act. COP27 could be considered a success if climate ambition is accelerated and there is greater focus on implementation, supported by the release of a more concrete action plan. Figure 3 below shows the key areas that will be considered at COP27.

Hard-to-abate sectors could pay for limited progress now

Current NDCs set an emission pathway that is insufficient to limit global warming to 1.5°C or even 2°C above pre-industrial levels by end-century. Delaying action will mean there is more to do later and this risks putting the world on a hotter climate path, locking in more severe physical climate risks. This compounds the decarbonisation challenge for hard-to-abate sectors.

The global transition to a low-carbon economy will create winners and losers. Real-world business and finance decisions are increasingly being driven by climate change considerations – a trend that will only accelerate. Current efforts might not suffice to meet our climate targets, implying more drastic and costly adjustments at a later stage. The cost of this inaction now will disproportionately fall on hard-to-abate sectors with high emissions in the future. These sectors will have less time to adapt and develop the necessary technologies to decarbonise and to put in place the needed infrastructure and investments.

So, do NDCs matter? The short answer is yes, these plans detail the direction of travel that governments are set on. These paths are only going to get more prescribed and difficult. While governments around the world are currently struggling with a myriad of new and urgent challenges, enhanced climate commitments at COP27 would help drive action and spur further investment into decarbonisation and green technologies.

Find out more about our Sustainability Services.

Our reputation as an independent and impartial authority means you can rely on our data and insights to answer your big sustainability questions.

Tell me more