China’s carbon emissions will peak before the official 2030 target date even without sharp increases in domestic carbon prices. The Chinese government can achieve much of its near-term emission reductions through energy consumption targets and measures within its ‘dual control’ system. Despite the energy price crisis, CRU does not believe that targets will be significantly relaxed; a more likely outcome is the expansion of the policy framework to incorporate carbon emission and intensity targets.

Achieving net zero by 2060 will be challenging. This will require more than existing measures can deliver. We forecast China carbon emissions will peak before 2030 and we expect that, after the peak, the Chinese government will rely increasingly on carbon pricing to achieve the emission cuts required to reach its carbon neutrality target by 2060.

An emerging country with advanced countries’ per capita carbon emissions

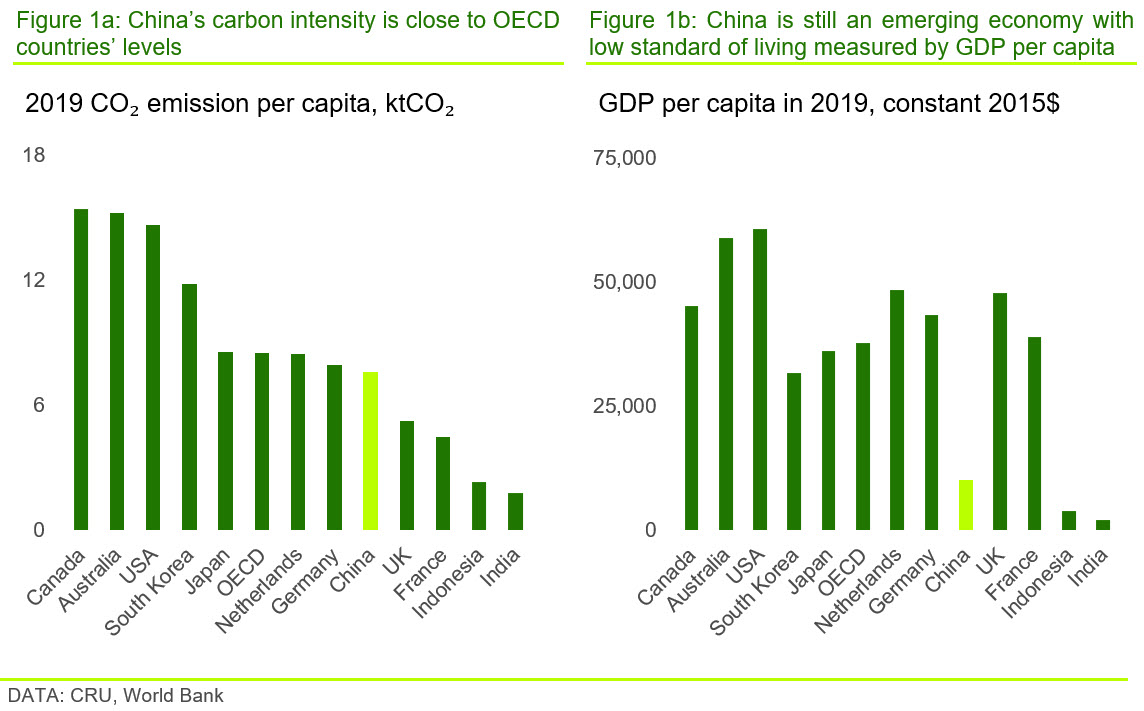

In 2019, Chinese carbon emissions per capita were higher than in most other emerging countries and close to the OECD average (Figure 1a). Given the country’s lower per capita GDP (Figure 1b), this reflects China’s high level of carbon intensity in the creation of value added in the economy.

Still, China is an emerging economy with a relatively low standard of living as measured by per capita output. Hence, its carbon emissions are increasing in line with developments seen in other emerging economies.

China plans to decouple economic progress from emission growth by 2030

The Chinese government plans to decouple economic development from carbon emissions growth and has set a 2030 carbon intensity target and carbon peak goal, whilst targeting continued economic growth, to achieve this.

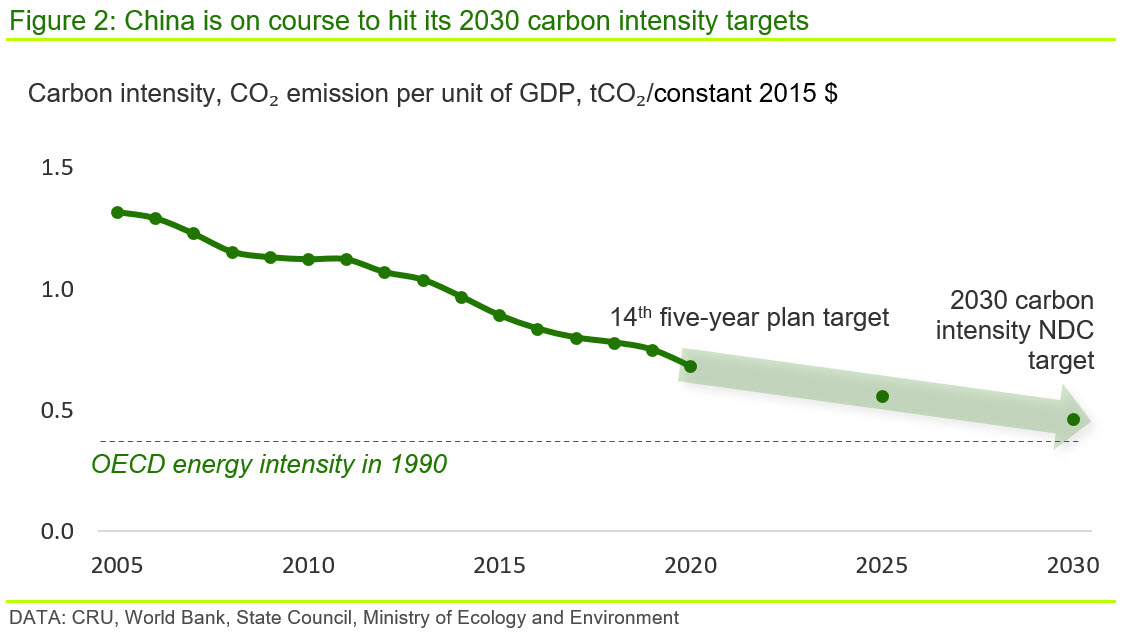

In the first Chinese Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) document, submitted in September 2016, China promised the carbon intensity of the economy would reduce by 60–65% by 2030 compared with 2005. Later on, ahead of COP26 in October 2021, China updated its NDC and additionally committed to a 2030 carbon peak target.

Having said this, given the past years’ efforts on renewable energy development, industrial restructuring and carbon emission management, China’s 2030 targets are not particularly challenging. By 2020, the carbon intensity of the economy had already dropped by nearly half (Figure 2), which suggests the intensity target will be achieved if China maintains this carbon intensity reduction trend in the next decade. Currently, this is planned through the adoption of stated policies such as provincial and sectoral ‘dual control’ policies. As a result, by 2030, Chinese carbon intensity should be similar to the OECD average in the 1990s, but what specifically are the actions they might take to achieve this?

Emission cut will mainly come from renewable power and industrial restructuring, not carbon prices

The carbon emission reduction in the next decade will mainly be attributed to renewable power displacing coal, increased use of scrap in the steel sector, an increasing share of less carbon intensive industries, as well as industrial emission reduction control.

Specifically, in the 14th five-year plan, China plans for a carbon intensity cut of 18% by 2025 compared with 2020. Among the expected 18% carbon intensity cut, according to CRU’s forecast, 44% will come from a lower coal share of power generation and the steel sector contributes 25% through scrap displacing coal and the declining share of China’s GDP coming from the steel industry. The remaining declines in carbon intensity will come from a shift to less carbon intensive industries and carbon intensity controls.

China has established measures, such as setting provincial and industrial energy efficiency improvement targets and control capacities of energy intensive industries, to ensure the national targets are achieved, but these measures are implemented at the provincial level. For example, when a power shortage occurred in Yunnan this summer, it was the energy intensive industries and high carbon sectors that were targeted to reduce energy demand.

The building of new capacity in carbon intensive industries will be less favourable at the provincial level because such new capacity will make it more difficult for local governments to hit their ‘dual control’ targets.

This suggests that the ‘dual control’ approach could be effective in helping China achieve the 2030 carbon intensity goals, even in the absence of stringent carbon prices.

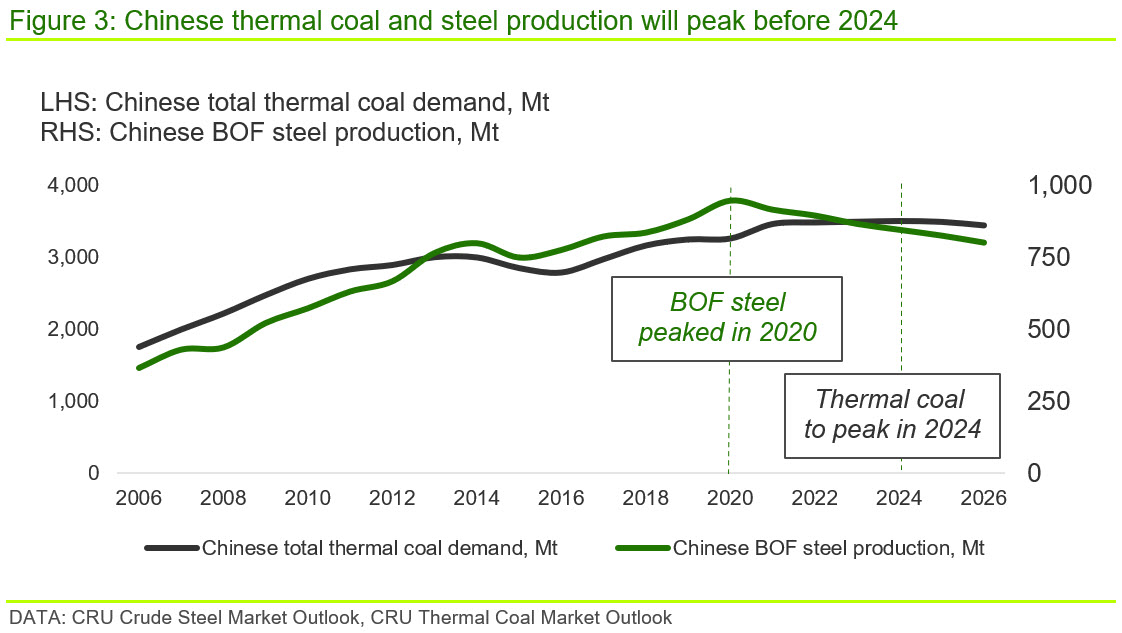

Reducing carbon intensity will help to slow the increase in emissions, but the overall level of emissions will also depend on the size and composition of the Chinese economy in 2030. We expect emissions in the Chinese thermal coal and steel sectors, which are the two major emitters, will peak by 2024 as a result of effective energy and carbon intensity management efforts and flat to easing demand (Figure 3).

The more challenging 2060 net zero target requires higher carbon prices

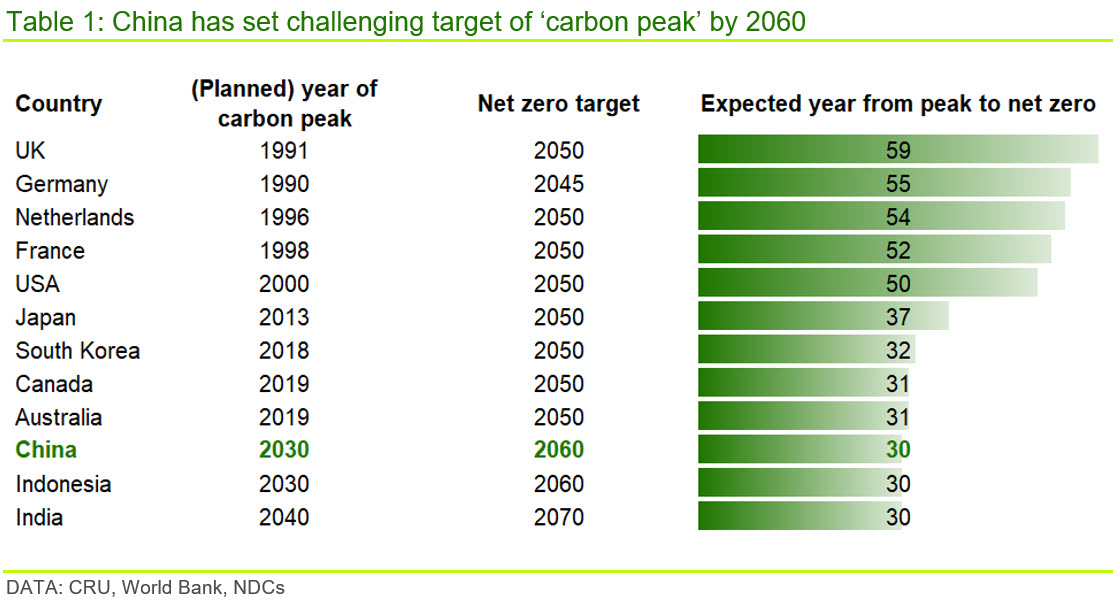

Although the 2030 targets are not particularly onerous given the current trajectory, China has set a challenging target to achieve net zero by 2060, only 30 years after its planned peak year. This is a shorter timescale than for most OECD countries.

Beyond 2030, we expect the government will need to rely increasingly on carbon pricing to achieve the necessary carbon emission reductions to hit net zero by 2060. This is because carbon emission mitigation solutions are generally costly and rising carbon prices are a powerful tool to help encourage businesses to invest in decarbonisation solutions.

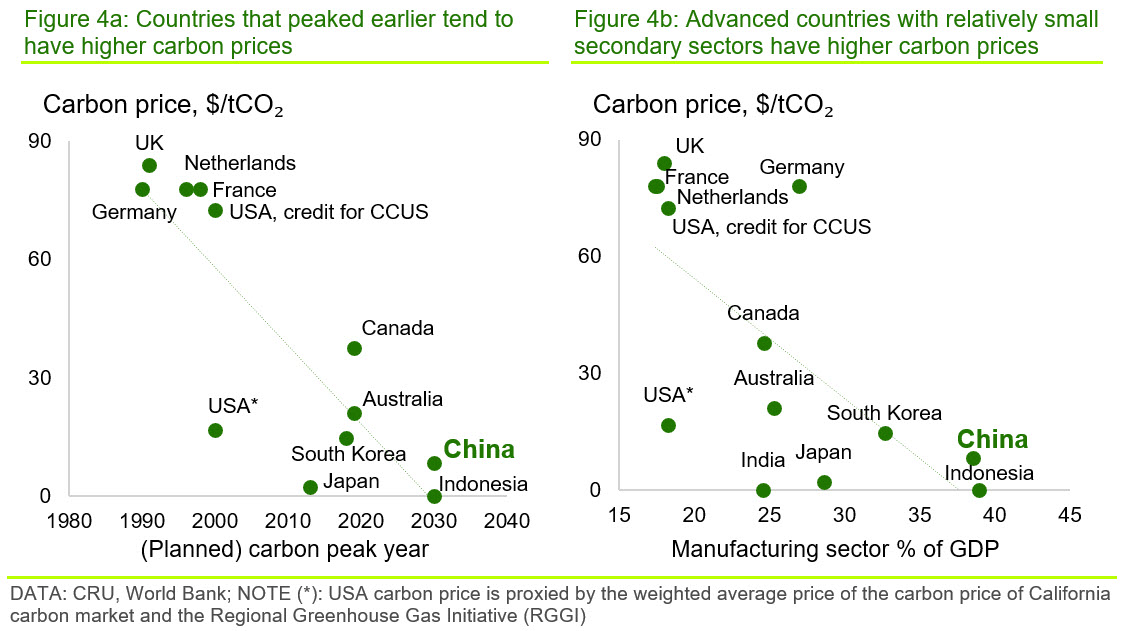

Carbon prices tend to be higher in countries that have already peaked in their carbon emissions than in those that have not (Figure 4a). They also tend to be higher in more advanced countries with relatively smaller secondary sectors, which mainly includes manufacturing but also economic activities such as construction and mining (Figure 4b). This reflects the fact that more advanced countries generally have relatively larger, less carbon intensive, services sectors.

We expect China will follow this track and will put greater emphasis on carbon pricing once it has passed its carbon peak later this decade and the economy shifts increasingly towards services. China established a national carbon emissions trading scheme (ETS) in 2021, which will be developed further for this purpose.

The carbon price on China’s national ETS remained at ~$8 /tCO2 in its first year of operations. This relatively low price is due to the currently abundant free allowances allocated to the power industry. Once the country has passed peak emissions in the late-2020s, we expect the Chinese carbon market to be developed further to cover more economic activities and to offer fewer free allowances.

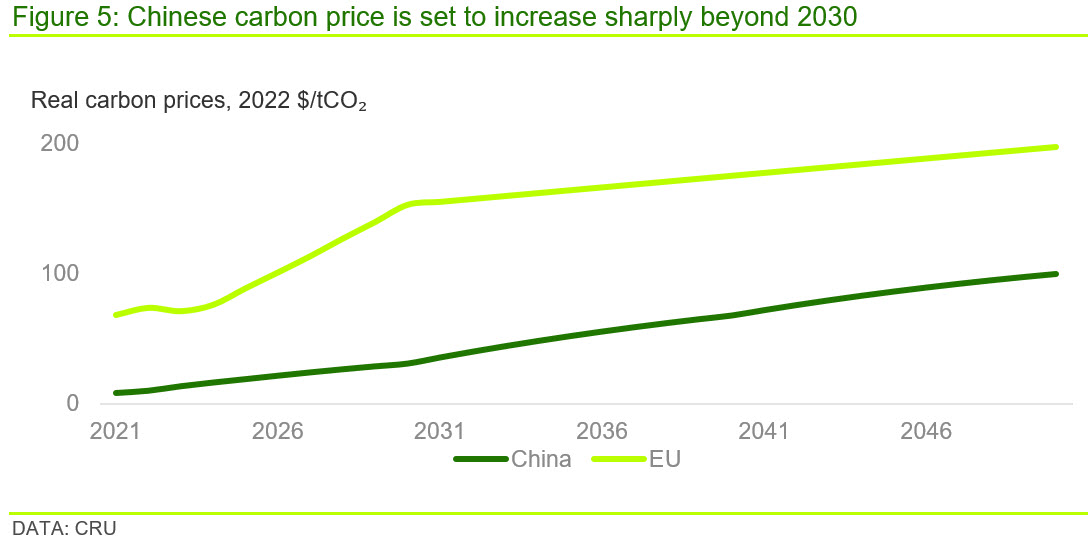

If the Chinese government wants to achieve its aims and carbon price is the main tool, then the Chinese carbon price would need to rise sharply to ~$100 /tCO2 (real 2022) by 2050 (Figure 5) to remain on track for the 2060 goal. This is the price needed to raise the cost of traditional fossil-based technologies such that sufficient low carbon options become economically viable to keep on track to achieve zero emissions by 2060.

We predict that the Chinese carbon price will be at around half of the EU carbon price by 2050, firstly because of the lower abatement costs in China, but also because China intends to achieve net zero in 2060, 10 years later than the EU and most OECD countries.

If you would like to discuss China’s decarbonisation policies and their impact on the industry, or if you want to know more about Chinese abatement cost, please get in touch with us.

Find out more about our Sustainability Services.

Our reputation as an independent and impartial authority means you can rely on our data and insights to answer your big sustainability questions.

Tell me more